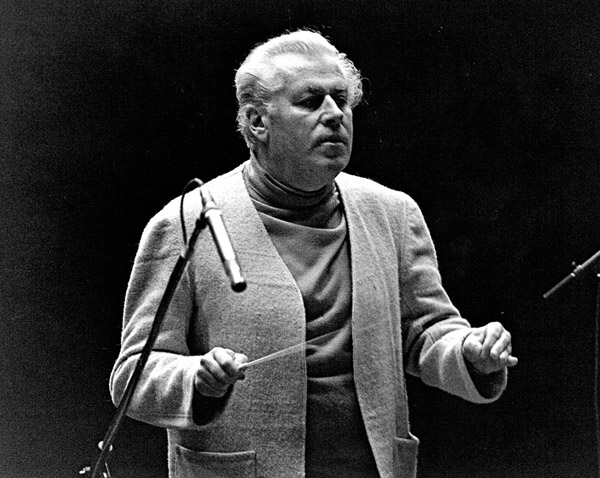

Symphonia Orchestra conducted by

Ludo Philipp

For some reason the music of Dolf van der Linden has largely passed me by, probably for the simple fact there wasn’t a lot of it about in my early years in New Zealand. I had to wait to come to England to discover it. Scottish comedian James Finlayson in Laurel and Hardy films unknowingly gave van der Linden a free plug every time his expression of surprise proclaimed “Dolf!”

Another musician I didn’t have a clue about was conductor Ludo Philipp. You won’t believe this, but he lived below me in his Kensington apartment for twenty-five years and in all that time I never met him. He probably had no idea I was working in the same business. I assumed he was Polish because after WW2 many of his countrymen settled in London.

From the very outset there’s no doubt that Cab Rank showed the composer must have been a Farnon fan, because Jumping Bean’s cheeky augmented 4th gets two quotes. In fact this jazz-influenced interval was a turning point in light music, inspiring many a Farnon piece. Oddly enough I can’t think of many other composers blatantly using it. Cab Rank from 1957 is an excellent example of a light orchestral piece in 1940s style. Also there’s something of Clive Richardson and Len Stevens about it. This jolly tune bounces along describing an obviously busy taxi rank. After the first 16 bars the strings go into a relaxed lyrical mode reminding one of the legendary Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra. After a little connecting passage, we’re back with the lively opening.

And then we go into the bridge with a strong unison string sound repeated in harmony with added brass. Before we return to the middle section proper, a bright and breezy fill-in section (a bridge within a bridge) with lots of triplets keeping things moving.

From the top again it’s that famous Farnon trademark making two more appearances and another chance to hear the delightful opening with its smooth expressive string sound (very innovative for the 1940s). It’s a pity the end itself wasn’t a tad more extended.

Cab Rank from “Melody Mixture”

Guild Light Music (GLCD 5197)

by Robert Walton

(Johnston, Coslow)

Robert Farnon’s arrangement analysed by Robert Walton

The period of the early 1950s when Decca recorded a series of LPs by Robert Farnon’s Orchestra playing some of the top standards of the “Great American Songbook” is now considered more than ever in the 21st century a genuine Golden Era of arranging. Paul Weston was the first to make mood music albums but Farnon took it to another level. Music lovers and professionals alike were astounded by Farnon’s total originality when he borrowed freely from his own compositional idiom, as well as creating something completely unique. But it was much more than that. It was as if he had been waiting for the right moment to introduce his style to an unsuspecting world. Everyone else’s arrangements suddenly seemed sort of average. His gift for giving these songs a new freshness and feeling transformed them into undeniable masterpieces.

I first heard Cocktails for Two in 1946 sent up by Spike Jones and his City Slickers with vocalist Carl Grayson, although it was introduced by another Carl, Carl Brisson in the 1934 film “Murder at the Vanities”. It was also part of the repertoire of cocktail pianist Carmen Cavallaro. Like Carmen I have always preferred the tune in a Latin American tempo. However the original dotted rhythm as in the sheet music sounds perfectly fine in Farnon’s foxtrot arrangement.

So come with me to revisit an old friend, or if you’ve never heard it, allow me to be your guide while we explore the wonders and unexpected pleasures of a Farnon score. It may not be the greatest standard but after Farnon has worked on it, Cocktails for Two was converted into something really special. Duke Ellington tried to give it a face-lift as Ebony Rhapsody but the best he could manage was a jazzed-up version of Liszt’s Second Hungarian Rhapsody.

The introduction of Cocktails for Two is a gem of an orchestral flight of Farnon fancy inspired by squeezing every ounce of emotion out of the melody and leading to a beautiful climax. In just a few short bars we have been transported to another world. Did you hear the tiniest touch of a violin before entering “some secluded rendezvous?” The flute first takes up the actual tune with excellent support from the orchestra and rhythm guitar. Then the oboe solos for four bars before handing back to the flute. The first 16 bars are surprisingly straight; always a sign that Farnon has something up his sleeve but is not prepared to give up its secrets just yet.

Still comparatively straight, the bridge is occupied by a tight, lightly swinging, close harmony muted brass choir with unison lower strings and celeste. When the tune resumes, the oboe is brought in again and for the first time something stirred in the Farnon universe. Underneath, the clarinet plays a slightly discordant series of notes but even more daring is the next chord change, B flat 9,11+ (actual notes B flat, A flat, C and E). He always knows just how far he can go in “clever clever” land.

Time for a second swell. The orchestra expands its horizons into some lovely key changes with a gorgeous surge of string power terminating in a flutter of woodwind. Returning to the middle eight, this time it’s the woodwind in block harmony supported by a string descant climbing into harmonics territory. Lazy lush strings in harmony take over the tune and in a more subservient role the oboe chatters away.

Quite suddenly you get the feeling that the end is nigh as the strings begin to slow down for the woodwind who recall the opening melodic phrase. And adding icing to the cake, a tender violin repeats the same set of notes.

Cocktails for Two from

“Two Cigarettes in the Dark”

Vocalion (CDLK 4112)

(Hubert Bath)

Analysed by Robert Walton

In the 1940s there was an outpouring of potted pieces for piano and orchestra written specifically for British films. These include The Dream of Olwen (Charles Williams) from “While I Live”, The Legend of the Glass Mountain (Nino Rota) from “The Glass Mountain” and just for a change the real Rachmaninov for “Brief Encounter” borrowed from the Second Piano Concerto. It was Steve Race who cleverly coined the phrase “the Denham Concertos” after the film studio that often featured such works on their soundtracks.

But there were three really outstanding Rachmaninov-inspired works for piano and orchestra, two from movie soundtracks. The most popular was Richard Addinsell’s Warsaw Concerto from the 1941 film “Dangerous Moonlight”. Then there was Clive Richardson’s independent composition London Fantasia (1945), a brilliant depiction of the Battle of Britain. The third, Hubert Bath’s Cornish Rhapsody from the film “Love Story” (1944) was another World War 2 composition that caught the public’s imagination mostly because of the music. It’s the story of a concert pianist, played by Margaret Lockwood, who learning she had an incurable illness, moved to Cornwall.

Apart from the title Cornish Rhapsody that gives away its location, two other connections with the piece have a distinct English west country association. The composer’s surname reminds you of the famous Roman city but his birthplace was actually Barnstaple in neighbouring Devon.

The London Symphony Orchestra conducted by the composer with pianist Harriet Cohen goes straight into the main tune. Then everything changes with sudden dramatic chords followed by a rippling run from Cohen who continues the theme. Back comes the orchestra until a solo violin produces a brief tender moment supported by an oboe, horn, and sustained double basses.

Now Cohen sensitively plays the melody on her own; the first time we hear it clearly. After the orchestra creeps in, she acts as decorator until a distinct break occurs. Heading for the heights, she goes into solo mode including some bird-like chirps in the treble (Messiaen would have approved). Then she gets heavy-handed working up a bit of a lather before quietly welcoming the orchestra back with some gentle highly technical pianistics. Thunderous percussion precedes the orchestra that spells out the tune in the strongest of terms. Cohen again joins up with some thrilling playing for some musical tennis, tossing the tune around with the orchestra. From there it’s all go to the end, building up to a colossal climax and giving the glorious main melody its final outing with soloist and orchestra coming together for a magnificent finale. That performance is guaranteed to make any audience applaud rapturously.

And that’s exactly the feeling I used to get each time I heard Cornish Rhapsody all those years ago. For me it was the best of the film piano and orchestra compositions probably because it was a simple tune yet at the same time so dramatic.

“The Composer Conducts” (Vol. 2)

“The Golden Age of Light Music”

Guild (GLCD 5178)

(Joyce Cochrane)

Analysed by Robert Walton

For me the name Joyce Cochrane has always been synonymous with just one composition, her beautiful Honey Child immortalized in Robert Farnon’s arrangement for the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra. So it was a nice surprise to come upon one that almost got away. Flowing Stream is included in the Golden Age of Light Music series in “A First A-Z of Light Music”. (Guild GLCD 5169).

With no intoduction the opening immediately calls to mind two great light orchestral classics - Clive Richardson’s Outward Bound and Benjamin Frankel’s Carriage and Pair. But this is Flowing Stream of 1958 played by the New Century Orchestra conducted by Erich Borschel. It was used in the same year as the theme for a British Southern Television series called “Mary Britten, MD”, starring Brenda Bruce. The juxtaposition of the two tunes works remarkably well in quite a different arrangement from the originals. Flowing Stream has a lighter textured treatment with a lovely feeling of peace and calm in a troubled world guaranteed to make you smile. Pure nostalgia you might say from a vanished era. Each time the strings go into a holding pattern, flutes ripple their way over the chord.

After 16 bars we go into 8 bars of a contrasting tune perhaps suggesting a change of scenery but with more tension. Listen to a descending string bass before the main theme repeats and completes a 32 bar chorus with a definite finish. In fact it’s a double closure of the first section.

And now the bridge. Modulating to a new key, a pleasant melody played by a horn provides clear echoes of the theme with a slightly bluesy effect but quickly returns to the delightful main strain. And then the tune (more laid back) is repeated yet again in two keys before going into that earlier 8 bar passage. Finally after a gentle restart the haunting Flowing Stream gradually builds up to a truly triumphant ending. By now it has become a fast moving river!

(Torch)

Analysed by Robert Walton

In the early 1950s when most people were requesting the top pop hits of the day, I was unashamedly asking for light orchestral numbers on the “Listeners’ Request Session” at our local radio station, 1ZB Auckland. I always signed my name “Blue Eyes of Remuera”. Anyhow, the very first record I requested was Going for a Ride by the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra. Incidentally Torch’s Radio Romantic was the programme’s signature tune.

I’m amazed I hadn’t already analysed Going for a Ride in one of my JIM articles, but it’s never too late I guess. This Sidney Torch classic happens to be the second item on David Ades’ introductory compilation of “Golden Age of Light Music” on Guild (GLCD 5101).

Going for a Ride starts straight in with nine identical bright staccato notes played by a mellow flute with the orchestra. Keeping up the interest and making sure the listener is concentrating, this catchy tune repeats itself in a higher key. Now comes what we’ve all been waiting for, the first of those thrilling Torch fillers. It’s almost as if the main tune is purely a prop inspiring a whole chorus of connecting passages - like a delayed introduction. It’s those crisp incidental interludes that are the lifeblood of these light orchestra gems. The reason we know them so well is that they were heard constantly as production music on newsreels, radio and television. To us light music enthusiasts, they were the soundtrack to our lives.

Analysing the aforementioned, the strings keep us on tenterhooks with some dramatic bow gestures. Woodwinds offer up some wonderfully rapid phrases answered by the strings and then we’re in true Torch territory with the brass blazing away in preparation for an imminent return of the opening tune.

Now it’s bridge time with first off, the Torch brass and strings enlivening things up, before an oboe’s plaintive tone adds its colour to the mix. Gradually the orchestra builds while Torch in his element is doing what he does best, exciting us with more of those imaginative ideas in his orchestrations. Never had light orchestral music been proclaimed so powerfully within a composition. Though the actual melodies might have acted as props they were extremely tuneful and appealing.

There’s no doubt the two top light orchestral talents in the 1940s and 50s in Britain were Sidney Torch and Robert Farnon. They were both original and prolific and towered above the rest. It’s a pity Torch didn’t arrange more music for the “Great American Songbook”.

(George W. Duning)

Analysed by Robert Walton

One of the most romantic scenes in cinematic history has just got to be the moment William Holden sensuously dances with Kim Novak in the 1955 film “Picnic’. From a laid-back piano/guitar quartet playing Will Hudson’s 1934 standard Moonglow, emerges George Duning’s glorious melody of the theme song from “Picnic”. This is one of the most effective musical juxtapositions of all time. The haunting orchestration was by Arthur Morton.

On the flipside of a Brunswick 78rpm disc No 05553 is the full version of the Theme from “Picnic” featuring the composer conducting the Columbia Pictures Orchestra. Although you’re getting your money’s worth in its completed form, to hear it with Moonglow is an experience not to be missed, particularly the constant jazzy phrase first heard in bars 7 and 8. The atmosphere is electric especially when the strings make their 6-note entry in ascending thirds in the key of C on the chord of A minor 9,11. So let’s take a closer look at this double whammy of keyboard and orchestra with Morris Stoloff conducting the Columbia Pictures Orchestra.

It’s the contrast of small group and orchestra that is the perfect musical balance for underscoring the action. The first time I heard the strings creep in was a total surprise and revelation. If the quartet with its Teddy Wilson-type piano had just continued playing while they were dancing it would have been satisfactory, but the bonus of strings added an extra ingredient to the mix, making it special. George Duning was spot on. This very lyrical strain was perfect for the job but Steve Allen’s words for the McGuire Sisters’ didn’t exactly catch on. The romantic aspect had been sealed with a “smooch of strings” which seemed to go on forever. The George Cates million seller wasn’t a patch on the other George’s version.

It’s difficult to explain why, but this is a typical Hollywood sound. Couldn’t be anything else. The ultimate in schmaltz you may say. Part of the explanation I think is the simplicity and yet the modernity of the melody. Perhaps it’s because it’s based on a song. After all, As Time Goes By literally made “Casablanca”. There are very few English movies that fall into that category. One that comes to mind was Malcolm Arnold’s “Whistle Down the Wind” theme but it didn’t have the American touch. The Los Angeles string sound is nothing like London’s. You just know when you hear it. It’s perhaps more alluring.

(Raksin)

Analysed by Robert Walton

Robert Farnon was one of the first light orchestral composers to come up with a most original idea. He found that a complicated beginning of a piece (almost atonal) not only provided a sense of risk-taking like a high wire act, but kept the listener guessing as to where it would finally alight in a normal tonal context. His Manhattan Playboy has all the elements of such a format in which the opening bars of the actual tune are a sort of boppish free fall before landing in the safety net of the home chord. The effect of all this was mind-blowing.

The same thing effectively happens in the haunting theme The Bad and the Beautiful from the 1952 film of the same name, although this is a much slower tempo. It’s a more meandering tune than David Raksin’s masterpiece Laura. For the first few bars of The Bad and the Beautiful we’re on a restless (some might even say “reckless”) Raksin flight of fancy with the blues overtones of Harold Arlen. This is a ravishing piece of writing and I was totally captivated. After all this tension, the “sun” suddenly comes out courtesy of a French horn and we’re at last happily ensconced in a key of contentment. Still in the same key a solo violin keeps us on the straight and narrow giving an edge to the music, enticing us back to the exotic. We’re immediately whipped away from our comfort zone by a dance band-sounding muted trumpet into a repeat of that elaborate opening.

Now strong strings in close harmony play an absolutely gorgeous middle section of crying and sighing. Perhaps it should be called a “bridge of sighs”. No need to consult your physician as it’s only a case of cutis anserina (goose pimples). A perfect moment to compare the much improved recording quality of the Rose Orchestra of 1953 with that of its first attempts just ten years earlier. I’ve never quite understood why the quality of Rose’s early work, both in performance and recording quality, was sometimes not quite up to scratch on those old 78rpm discs. Other orchestras of the same period seemed to produce better results.

The sensitive violin is back for 5 bars of the start, after which the rest of the strings bring us neatly to a conclusion, and on the way, echo the opening of Artie Shaw’s Frenesi. However we’re still not quite finished as the horn quotes the opening.

This has been an extraordinarily sublime experience and one that I am unlikely to forget. Hollywood and Raksin are at their best. We owe an enormous debt to film soundtracks.

The Bad and the Beautiful (Raksin)

David Rose Orchestra

“Great American Light Orchestras”

The Golden Age of Light Music

Guild (GLCD 5105)

POLKA DOT

(Eric Cook)

Analysed by Robert Walton

Whenever serious light music is discussed, the conversation inevitably turns to the finest orchestra in the genre, the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra. And it’s not just the standard of playing - that goes without saying. It’s also those unique compositions written by the top writers of the 1940s and 50s - Sidney Torch, Charles Williams, Clive Richardson, Wally Stott and of course Robert Farnon. In comparison with the premier production company Chappells, which made these marvels, much of the music of the minor mood labels was corny, predictable and frankly amateurish. Occasionally though, one comes across a piece which could have come straight out of that elite stable. Eric Cook’s Polka Dot is one such title that has all the elements of a QHLO standard about it, and well describes one of a number of round dots, repeated to form a regular pattern on fabric. Come to think of it, professional musicians often refer to musical notes as ‘dots’.

The slick string introduction might sound like a main melody but after 8 bars it soon becomes obvious the official tune, beautifully supported by a subliminal counter-melody, begins at bar 9 after some muted brass sets the scene. Then a very playful Farnon-like flute requiring absolute virtuosity gives the introduction a woodwindy boost followed by a lovely fill section. Then the strings imitate the flute. And just before the tune reappears we’re treated to another few bars of delicious close harmonies. It all sounds so totally 1940’s treasure trovish and the constant bustling motion almost takes your breath away.

Immediately after that busy opening, the orchestra goes into rest mode for a typically rich vocal-like sweeping middle section with strings, first in gorgeous close harmony then the bare tune. Even in 1957 the David Rose influence was present. And before we know it, we’re back to the beginning for a repeat. The tune of Polka Dot is gradually brought to a logical conclusion but near the end it’s suddenly interrupted by some more thrilling bravura playing from the flute before coming to a final stop.

Polka Dot is one of the most satisfying little light orchestral workouts I know, and British composer Eric Cook deserves high praise.

Polka Dot (Cook)

New Concert Orchestra/Cedric Dumont

“A Box of Light Musical Allsorts”

Guild Light Music (GLCD 5157)

CENTENARY CELEBRATION

Robert Farnon’s 100th birthday

By Robert Walton

July 24th 2017 is exactly 100 years since Toronto-born Robert Farnon first saw the light of day. Much of my knowledge and praise of him has trickled down through my JIM articles especially in the miniatures. It’s amazing what one learnt from the music. Bob used to regularly ring me with a comment or two about my latest article. He appreciated my musical analyses and sometimes gave me details of the back-stories of his Canadian impressions.

Why does music move us? It’s a very personal thing really. There are many reasons we are affected, mostly impossible to fathom, but in Farnon’s case it’s a totally spiritual experience covering all the emotions especially in his magnificent miniatures. The great JS Bach affected us in much the same way. Farnon’s might be brief but they contain such a huge range of melodic and harmonic originality that they come up fresh every time. Each aspect of the music sends out an unspoken message of positiveness and hope. Normal language ceases to exist as the music does the talking.

Take Melody Fair for example. This radiant classically orientated two and a half minute masterpiece demonstrates Farnon’s natural sense of musicianship in which every element slots perfectly into place. Like a river it flows beautifully from start to finish. There never was or indeed ever will be such perfectly formed pieces of creativity. Strangely you get more for your money with a miniature.

In Farnon’s obituary I omitted to mention his arrangements of popular songs from shows and films. It was the first time many overseas fans ever heard his work. However they were generously sprinkled with the seeds of his miniatures.

It’s hard to believe 100 years have passed since he came into the world but his music from symphonies and film soundtracks right down to those towering miniature masterpieces, continue to excite the old guard and thrill the up-and-coming generations,

Although Robert Farnon is generally regarded as the greatest arranger of his generation, he surely must also be a strong contender for the title “Greatest Miniaturist of the 2Oth century”. Just as Bach’s 48 Preludes and Fugues, each lasting only a few minutes, is an entire world of music in miniature, so too are Farnon’s light orchestral pieces. Unfortunately because of his association with background music and particularly signature tunes, he never received the serious recognition he deserved. Only when his music is completely divorced from its original purpose and treated independently on its own merits, will it be properly appreciated. It may take a little time, but make no mistake that will come.

As well as his memorable music, it is not generally known that many musicians and arrangers including myself have reason to be grateful for his generosity with help and advice.

Happy 100th Bob!

(Gilbert; Sullivan)

Robert Farnon & His Orchestra

Analysed by Robert Walton

There can’t be many arrangements that have such a variety of musical nuts and bolts - Canadian Caravan, “James Bond”, “Maytime in Mayfair”, Count Basie, Fred Astaire and Gilbert and Sullivan. The opening alone is one of the most thrilling in music taking full advantage of the arrival of stereo. You’ve never heard strings, brass and woodwind like it. Purists of comic opera were not exactly pleased but American audiences enjoyed Mike Todd’s “The Hot Mikado”, his first Broadway musical in 1939.

And then the orchestra swings like the clappers in a way that the original “Mikado” never did and never will again. A toe-tapping rhythm grabs you everytime and instantly brings back Gilbert’s lyrics in a most unexpected setting. And talking of feet, we’re treated to a dazzling display of ‘Astaires’s wares’ after which the ghost of Count Basie bounces in. (I once met Robert Farnon at a 1957 Basie concert in which he described the sound as “a shot in the arm!”).

The piece gradually builds up to a terrific climax influenced by the orchestra long considered one of the world’s best swing bands Count Basie, on a par with Duke Ellington and Jimmy Lunceford. The Farnon sound still bears the stamp of Kansas City. The brass belts away with the strings having the final say.

Let’s remind ourselves of those clever catchy words we heard in our youth.

My object all sublime

I shall achieve in time-

To let the punishment fit the crime,

The punishment fit the crime;

And make each prisoner pent

Unwillingly represent

A source of innocent merriment,

Of innocent merriment.

My Object all Sublime (Gilbert & Sullivan)

Jack Saunders Orchestra (actually Robert Farnon’s Orchestra)

“A Box of Light Musical Allsorts”

Golden Age of Light Music

Guild Records GLCD 5157