CD Review - Nicola Benedetti

CD Review - Nicola Benedetti

Baroque

Decca 4851891 [52’26]

It was not my intention to review this album here but then I read what Nicola Benedetti had written in her introductory notes, that "Many find it (the Italian baroque) light fare: too populist, repetitive and predictable." So maybe, putting these descriptions aside, it will appeal to our reader.

CD Review - Sumertime

Isata Kanneh-Mason piano

Decca 4851663 [62’52]

My last review was of a new release from one of the world’s best-loved queens of the keyboard and now we have this album of 20th century American music from a princess of the piano. Aged 25, Isata is the eldest daughter in the remarkable Kanneh-Mason musical family.

My last review was of a new release from one of the world’s best-loved queens of the keyboard and now we have this album of 20th century American music from a princess of the piano. Aged 25, Isata is the eldest daughter in the remarkable Kanneh-Mason musical family.

(Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein II)

Peggy Lee

Analysed by Robert Walton

Whenever I’m asked to name one of my favourite songs in that largely neglected period, the Golden Era of Popular Music between 1920 - 1960, without hesitation my reply is always The Folks Who Live on the Hill sung by Peggy Lee.

(Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein II)

Peggy Lee

Analysed by Robert Walton

Whenever I’m asked to name one of my favourite songs in that largely neglected period, the Golden Era of Popular Music between 1920 - 1960, without hesitation my reply is always The Folks Who Live on the Hill sung by Peggy Lee. But as you’ll find out there’s a heck of a lot more packed into just one short track. For some reason the location in my imagination has always been the Tauranga region of New Zealand’s Bay of Plenty - a truly rural spot a few miles inland from the mighty Pacific Ocean. What a setting and what a singer! So much so, I simply can’t wait to proceed with my analysis. Before that though I must tell you the song was composed in 1937 and first sung in the film “High, Wide and Handsome” by Irene Dunne. Twenty years later in 1957, Capitol Records revived it for surely what must be the definitive version, which is not surprising with all the talent involved.

This Mahler-inspired hymn-like miniature miracle begins with strings and harp creeping in to create one of the most beautiful feelgood atmospheres ever heard. The whole thing is cradled by Nelson Riddle’s brilliant score. And as if that isn’t enough, a solo trumpet pops up proclaiming something of great importance is about to be announced. Then a haunting oboe continues this short introduction via more trumpet with an added horn bringing the section to a close. (It reminds one of Western movie music).

Husky-voiced Peggy Lee now delivers Hammerstein’s glorious lyric making a very ordinary scenario quite special, with Kern’s equally gorgeous melody. Plan A, building a home on a hill has overtones of the TV series “Grand Designs”. The 43 bar tune including a bridge of 6 bars might be unusual but the overwhelming message is one of complete normality. Peggy sings about two people falling in love, bringing up kids and refers to many things families experience during one’s life. Every time she mentions the title, that trumpet joins her and goose pimples magically appear. And she insists on being called “folks”. No problem. We will oblige. It’s more like a prayer of thanks and hope for the future.

Oh yes, I almost forgot one small detail. Frank Sinatra waved the baton over the whole affair! At this difficult time of Covid and Climate Change, it was like a breath of fresh air!

CD Review – Love Songs

CD Review – Love Songs

Angela Hewitt piano

Hyperion CDA68341 [75’57]

We are constantly being encouraged to meditate during – and beyond – these still uncertain times. Researched, put together and recorded during lockdown, this album with its musical declarations of love across the centuries would be an ideal accompaniment to any such activity.

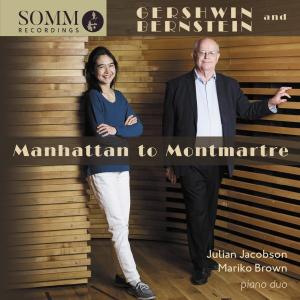

CD Review – Manhattan to Montmartre

CD Review – Manhattan to Montmartre

Gershwin and Bernstein

Julian Jacobson, Mariko Brown piano duo

Somm SOMMCD 0635 [72:30]

Recorded in August 2020, this is another non-orchestral release possibly brought about by the Covid lockdown – and another successful foray into our kind of music for the enterprising award-winning Somm label.

It is with profound sadness that we record the death of Vernon Anderson, who peacefully passed away on June 15th, after a period of ill health borne with great courage and dignity.

It is with profound sadness that we record the death of Vernon Anderson, who peacefully passed away on June 15th, after a period of ill health borne with great courage and dignity.

A native of Benfleet, Essex, Vernon was educated at Bearwood Royal Navy School in Berkshire and saw military service with the RAF, being stationed in the (then) British colony of Aden (now Yemen). Returning to Benfleet, he became a member of the Barking Choral Society, where he met his future wife Beryl and they married in 1971. Sadly, Beryl passed away in 2005, after having been cared for by Vernon during her terminal illness.

During the 1980s and 1990s, he worked as an Architectural Technician for the London Borough of Newham, but took early retirement. He then volunteered as a care assistant with the Alzheimer's Society and eventually became employed by that organisation.

Vernon had been a stalwart member of the Robert Farnon Society, attending almost every meeting for many years, and regularly presenting as well. He enjoyed, and had a wide knowledge of, many different musical genres, including of course Light Music, particularly that of Robert Farnon and his contemporaries. One of his great 'loves' was jazz piano and he often championed the brilliant playing of the very talented Scottish pianist Bill McGuffie.

I was always very appreciative of Vernon's assistance at RFS events, for he frequently helped me to dismantle, pack away and load the Audio-Visual equipment into my vehicle at the end of each afternoon's programme. It gave us a good opportunity to talk about music – and architecture, another of our mutual interests.

Although more recently he was no longer able to attend the London meetings at the Lancaster Hall Hotel, we kept in intermittent touch by telephone. I visited him during the summer of 2020 at his home near Ilford, just before he relocated to assisted living accommodation in Basildon. He was later hospitalised, before ultimately being moved into a nearby high-dependency nursing home, in March 2021.

Vernon was a thorough gentleman – and indeed a very gentle man. It was an absolute pleasure and privilege to know him and he will be greatly missed. On behalf of all former RFS members and LLMMG attendees, our sincere condolences are extended to his daughters Lynda and Claire and his son Keith – who, back in the 90s, also supported the Robert Farnon Society meetings at the Bonnington Hotel.

© Tony Clayden June 2021

CD Review – Bomsori

CD Review – Bomsori

Violin On Stage

Bomsori Kim (violin)

NFM Wroclaw Philharmonic | Giancarlo Guerrero

DG 4860788 [72:56]

To those who have already come across her, Bomsori Kim is recognized as one of today's most dynamic and exciting violinists. She won prizes at ten international violin competitions during the 2010s, and is a superstar in her homeland of South Korea. She was given her distinctive first name by her grandfather – it translates literally as 'sound of spring', although she was actually born in December 1989.

Magical Memories for Trumpet and Organ

Lawo Classics LWC1216 [67:50]

'This is the third album by a trio of female trumpet players – Alison Balsom and Lucienne Renaudin Vary being the others – I have had the pleasure of reviewing here. Tine Thing Helseth (born 1987) is a Norwegian soloist, who has been the recipient of critical praise across six continents and numerous awards for her musical work.

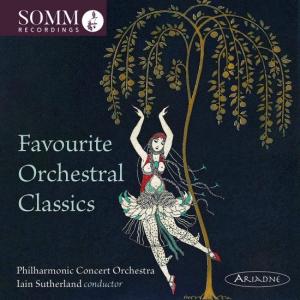

Philharmonic Concert Orchestra / Iain Sutherland

Philharmonic Concert Orchestra / Iain Sutherland

SOMM ARIADNE 5012 [78’25”]

My review of the last album by these artistes* finished with "… let us hope that Iain might have some more similar tapes in his archive", and here we are: 19 tracks recorded in Munich (June 1988) and Hanover (December 1992). Few conductors are as accomplished as the veteran Scot in the lighter orchestral music on this release.